How To Turn Your Clinical Supply Chain Pandemic Learnings Into New Best Practices

By Haneen Mazahreh-Boivert, OptiNose

Pivoting became not just a buzzword but a necessary skill for survival during the pandemic, and this rang especially true in the clinical trials world. Pivoting, navigating, and problem solving in real time led to many real-time lessons that have evolved into adapted best practices in the global clinical supply (GCS) space. With laxer restrictions both locally and globally, weaving new best practices into existing processes, and noting the reasoning behind them, will prove to be invaluable.

The global clinical supply chain is vast and encompasses several source areas, from planning and forecasting to operations planning, global distribution & logistics, and interactive response technology (IRT) system design, etc. Challenges were plentiful and faced head on, and this led to several realizations as we pivoted in the pandemic-driven clinical trial world. This article discusses how what we learned during the pandemic informs new best practices that can help us navigate a difficult landscape, including advocating for end-to-end clinical supply chain transparency and cooperation with peripheral stakeholders in ClinOps, quality, regulatory, etc.

The New Demand Curve

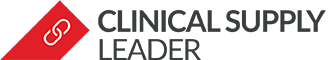

For planners in the GCS space, the site consumption curve on the left in the figure below is what is typically experienced in a clinical trial during non-pandemic times. When sites are open for the normal five business days per week, the on-site inventory is consumed over time; in the example below, it takes about six days to consume 10 kits. When the lower limit (or floor value) of five kits is reached on day three, it triggers a shipment of kits, giving the supply chain time to restore the site inventory of 10 kits by day six, avoiding a lapse in supply. The gradual consumption over time allows for adequate shipment time.

During the pandemic, a new consumption curve shape appeared, the one on the right below. With sites only open one or two days a week and completing all of the patient visits in a compressed amount of time, all of the on-site inventory could be consumed in a day, leading to a potential lapse in clinical supply (much like the toilet paper shortage of 2020). In this case, the floor value of five kits is reached and a resupply triggered on day three, but the rest of the site inventory was consumed by day five, prior to the resupply being delivered. The hastened consumption did not give the system a chance to trigger and ship kits in time to avoid a lapse.

Once the new consumption curve is recognized and inventory managers start using it as the demand curve shape for planning purposes, one can synthesize several solutions. Such solutions include simply increasing the floor values, which would lead to more drug product at sites for a longer amount of time. Disadvantages to this approach include potential waste at underperforming sites and feedback from sites regarding real estate issues and requesting to return or destroy drug product.

Another solution is to send all of the predictive demand to the site, letting them know that they will receive the predictive investigational product (IP) at the beginning of the trial. That still leaves non-predictive demand in jeopardy, and site real estate limitation is still a potential issue.

Therefore, the most appropriate approach for this demand issue is to really understand the expected enrollment rate and pattern by working closely with ClinOps and CRO partners. At any given point, there are three or four colleagues working closely with the site who have a plethora of information that would inform site enrollment and pace. The feasibility data, site location, site type (private clinic or hospital), foot traffic, whether the principal investigator is a key opinion leader in the field, previous experience, number of days per week dedicated to trials – all of these specs can indicate the expected demand for the site. With the pandemic behind us, sites can be asked if they plan to only open one day a week, or if they need drug product shipped out daily, etc. Working with the study leads and CRAs that have direct access to the site and this information, you can categorize sites as high, medium, or low enrollers. Generate demand curves over time and update the demand curves based on real data throughout the trial. Based upon those, you can set appropriate floors and ceilings that will set the sites up for success.

Packaging Operations: Planning, Manufacturing, And Distribution

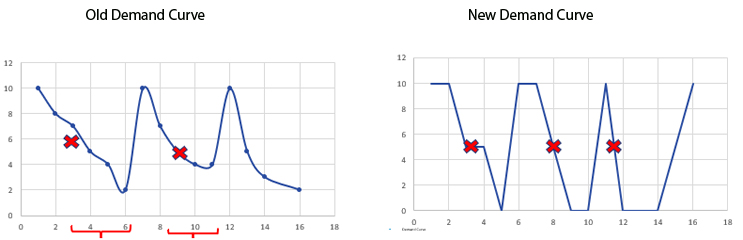

For the GCS operations team, planning for packaging runs is usually based on quantities of clinical supplies needed over time. Inputs such as enrollment rates, numbers of sites, dispense visits, etc., are used to calculate the amount of product needed to support the trial over time, either via Excel sheets or simulation programs. Then, other factors such as expiry dates and bulk inventory are considered while packaging runs are scheduled either internally or with a packaging partner. Typically, the main output of the operations plan is N, or the number of kits needed for each treatment group. In the example above, the total N for the study is about 375, and the three red circles are the scheduled packaging operations of N=175, N=125, and N=75. These plans are typically updated as the study progresses, new sites add or drop, new countries join, shelf-life changes, etc.

The challenge that arose during the pandemic is that resupplies could be put on hold indefinitely. This would lead to starting a patient on a drug and potentially not being able to complete the treatment – the dreaded interruption of supply for a dosed patient. One manufacturing partner I am familiar with had to halt production in order to manufacture hand sanitizer per government mandate to keep up with the global demand. It’s difficult to package when the bulk drug is not available, and difficult to keep patients in treatment if we don’t have packaged investigational product to give them.

The lesson from this challenge is that when planning packaging (or manufacturing) operations, in addition to considering the N, or the number of kits output, also consider P – the number of patients that can be supported with available supplies in case the world stops again. During the pandemic, clinical teams and sites pivoted and quickly adopted direct to patient shipments, so although the world’s supply chains were on hold, the site-based clinical supply chain kept moving in order to avoid lapses in supply for subjects already on a drug, all in an effort to have them complete the trial and salvage the data. The learning here is to ensure that packaged drug product at a depot should always be sufficient to allow enrolled patients to complete their program – hence, considering P in addition to N.

An overly simplified example of considering N as well as P when scheduling runs is as outlined below:

- N in this example is 60 kits of drug. Each kit lasts one month.

- P is the number of patients in given countries that can be supported with said supply at the depot.

- The N, 60 kits, can support the enrollment of 60 patients over one month. This N could also fully support six patients for 10 months.

Therefore, when completing inventory assessments or depot balancing, one should ask, is there enough packaged inventory to support the currently enrolled patients in a location that will ship to them? If resupplies are not possible, are the local depots set up in a way to support enrolled subjects and avoid loss of their data? Although global clinical supply groups typically manage inventories and IP, one must also monitor patient numbers to ensure depots have sufficient supply to support enrolled patients if resupplies cannot be scheduled or delivered. This again highlights the importance of working with ClinOps and CROs in order to have access to this information. This can be done by attending sponsor calls or pulling information from interactive web response system (IWRS) or electronic data capture (EDC).

In order to support the approach above, there must also be a clear line of sight to the bulk inventory as well as good communication with the manufacturing group. From a manufacturing perspective, there must also always be bulk on hand in case manufacturers are mandated to produce under the Defense Production Act or global supply chains lag or halt. One would expect push back for this “overage” of supply that may or may not be used, but it can be justified if it is positioned as insurance instead of overage, citing the pandemic and supply chain challenges as potential issues. In addition, having more than one manufacturer of your product is always encouraged for virtual companies, and at least the ability to manufacture key products in-house is suggested for larger companies.

When it comes to the regulatory filings, work with the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) authors to build in maximum flexibility. That is, ensure each investigational medicinal product dossier (IMPD) version includes all information for any lots that can potentially be used in trials (manufacturing location, API, methods, etc.), even if that bulk is not currently being used in that country. One must always be set up to pull in bulk anywhere, where allowed. This will require working closely with the manufacturing team and regulatory authors to explain the importance of this flexibility. It would be unfortunate to have available bulk that could technically be used in a country, but after undergoing a slight equipment change, the new version is not captured in said country’s IMPD, which renders the bulk un-releasable in that country. The U.S. IMPD typically has rolling updates, but the ex-U.S. IMPDs should be updated as well. There is a cost associated with this, but again, it is essentially insurance that guarantees flexibility across the supply chain.

In the final step of the supply chain prior to the drug finally reaching the patients – distribution – direct to patient shipping has seen an exponential increase, a topic that requires its own article to fully vet the details. Ensuring patient privacy is key here as kits are shipped directly to the patient’s home address. If the sponsor’s courier account number is used and the courier bill is sent to the sponsor, there could be a potential to reveal a patient’s private information or identity.

IRT Considerations

For IRT system design, typical fail safes such as unscheduled visits proved beneficial. Also, with the amount of information gathered in systems that support the trials and supply chain, having worked cross-functionally with other groups and vendors to delete redundancies will be useful, too. For example, the IRT group should work closely with the EDC group early in the design stage to ensure there is as little redundancy as possible. This will avoid unnecessary reconciliation and updates at the end of the trial, as well as audit findings for validated systems not being aligned. When possible, the IRT and EDC system should be linked and integrated, this alleviates the manual data input and relieves the sites of a repetitive step.

During the pandemic, our internal team found themselves downloading the IRT subject visits reports and manually adding the future patient visits, dates, drug to be dispensed, as well as visit procedures. In designing future IRT reports, consider including a projection report that will predict and complete the estimated future patient visits and aforementioned information. The IRT system already makes these calculations when predicting next visits dates and drug required for shipments; the report will simply be a way the end user can view and utilize this information.

Vendor Management

Vendors had the opportunity to differentiate themselves during the pandemic. Some vendors were in the proverbial boat and were quick to react, did not charge change fees, and acted in a true all-for-one fashion (and these vendor partners will be noted and remembered). Other vendors took the opportunity to jack up pricing and, as such, a new best practice is to include “pandemic clauses” in future contracts. These pandemic clauses can be flexible and should serve the specific purpose of offering protections for future pandemics, and they should at least be a point of discussion during the contracting stage.

Also, including pandemic key performance indicators (KPIs), such as responsiveness, reaction to a pandemic (or other such event), monetary impact, timeline impact, disruption extent, prioritization/customer service, to be discussed during business review meetings or governance calls is an additional best practice. KPIs that would alert the vendor to expectations up front and serve as a measurable way to assess vendor support are vital for measuring success during the project. When it comes to vendor contracting, ensure that contracts are set up directly between the sponsor and vendor (manufacturing, packaging, labs, distribution, IRT) instead of using a CRO as a middleman. This provides the opportunity for direct oversight, heightened visibility, control of finances, and greater impact and leverage. Finally, when curating an approved vendor list, ensure that there are small, medium, and large vendors on the list so that any activity can be assigned with flexibility. Smaller vendors can typically quickly react to smaller requests, and larger vendors are robust enough to support larger projects; having that flexibility to select vendors based on a fit-for-purpose approach could prove invaluable.

About The Author:

Haneen Mazahreh-Boivert is a global clinical supply expert and end-to-end supply chain advocate with more than 15 years of experience. Throughout her career, she has worked and consulted for numerous companies of varying footprints, including British Petroleum, Schering-Plough, Merck, Celgene, KMPG, and OptiNose. She is the founder of Pivot Consulting and Services and is a graduate of the American University, Rowan University, and Yale University with a B.S. in chemical engineering, a M.S. in chemical engineering, and a Certification of Executive Leadership, respectively. She is active in women in engineering groups.

Haneen Mazahreh-Boivert is a global clinical supply expert and end-to-end supply chain advocate with more than 15 years of experience. Throughout her career, she has worked and consulted for numerous companies of varying footprints, including British Petroleum, Schering-Plough, Merck, Celgene, KMPG, and OptiNose. She is the founder of Pivot Consulting and Services and is a graduate of the American University, Rowan University, and Yale University with a B.S. in chemical engineering, a M.S. in chemical engineering, and a Certification of Executive Leadership, respectively. She is active in women in engineering groups.